The saying goes that best things in life are free. But there are some pretty fabulous things that are not free, actually far from it.

Things that are expensive:

Seven nights at this holiday house at Port Douglas – $30,000 (off-season, of course)

Gucci Soft Stirrup Crocodile Shoulder Bag – $35,000 (and I bet I’d still not be able to find my keys unless I tipped the whole thing out)

Bottle of Dom de la Romanee Conti St Vivant Grand Cru Cote Nuit Vosne Burgundy – $38,000 (will still make your teeth and tongue go purple, but in a really fancy French way)

There are also some really shit things that are really fucking expensive:

Cancer.

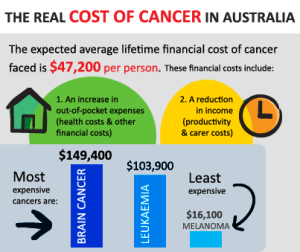

On average, cancer costs the patient $47,200 out-of-pocket. That is, $47,200 which is not covered by Medicare or private health insurance (if you have it). $47,200 that you either have to pay out in direct medical expenses such as specialist visits, surgeries, treatments and medications, travel expenses, increased need for child care, ongoing need for specialist devices and prosthetics (aka the actual boob in the actual box), or that you lose because of time off work for either you, or your carer, or both.

The amount cancer costs an individual varies on the type and stage of cancer and their life situation. In my case, in terms of actual medical expenses, breast cancer is one of the cheaper cancers because it is common and the treatments are readily available and therefore not as expensive. It also doesn’t require a lot of medical imaging tests, unlike many other cancers such as those within the organs. Having said that, my cancer was at an advanced stage and so my treatments were complicated and heavy-duty. My out-of-pocket medical expenses added up to just over $12,000 in eight months.

I have premium private health insurance, which covered the bulk of my $48,000 total treatment bill, but I still had to fork out for the many gap amounts which have to be paid by the patient, and then there was the cost of a seemingly endless array of medications. These medications aren’t actually to treat the cancer (as the chemotherapy drugs are paid for by your health insurance), but rather are to treat the side effects of the cancer. Endone for pain, steroids to boost immunity, temazepam for insomnia caused by the steroids, neulasta to prevent infection, SM-33 gel for mouth ulcers, silver sulfadiazine for radiation burns, amoxicillin for post-radiation burn infections …. and there’s your $12k gone.

As well as the $12,000 spent on medications, I lost in excess of $50,000 in income, as my income protection insurance did not cover my full salary. At the time of diagnosis I was the sole income earner, yet despite losing a breast, all of my hair, a fair amount of my sanity and more than $60,000 in the space of a year, I am one of the lucky ones. I could afford to pay for everything I needed. I had some income protection insurance. We were well ahead on our mortgage and were able to access that money to pay for my out-of-pocket expenses. We lived close to treatment centres so travel and accommodation did not have to be paid for. Dave put his degree on hold and found a job quickly that thankfully had the flexibility to enable him to care for our young child and me. We took a financial hit, but we have been able to come back from it. This is not the case for many people, and it will continue to get worse if the planned changes to Medicare go ahead.

The recent federal budget announcement in Australia was followed by a shit storm in the media about the mooted changes to Medicare. Most of the media coverage, and the associated discussion on social media, was about the government’s plans to introduce, from July 2015, a $7 co-contribution charge for GP consultations and out-of-hospital pathology services, and an extra $5 towards the cost of each PBS prescription. What did not get much attention or discussion was the proposed changes to out-of-pocket costs for medical imaging such as CAT scans, MRIs and x-rays. The Australian Diagnostic Imaging Association says as a result of the budget most patients will have to pay $90 upfront for an x-ray, $380 for a CAT scan, up to $160 for a mammogram and up to $190 for an ultrasound. A PET scan will cost over $1000 upfront. Whether you are a public patient (with some exceptions) or have private health insurance is irrelevant. These will be your upfront payments.

If you have, for example, advanced bowel cancer, you may require some sort of scan every 2-3 weeks during your treatment, which can go on for years. You may require a CAT scan one week, and a follow-up PET scan two weeks later. If these changes to Medicare proceed, you could be facing an outlay of $1380 every month just for basic testing. It should be stressed that this testing is not being done for shits and giggles (pardon the arse cancer pun there), it is being done so that decisions can be made about the type of treatment needed, and whether treatment is working or needs to be adjusted. Cancer patients universally hate scans because of the enormous and soul-destroying anxiety caused by the wait for results, so having to pay thousands of dollars each month for a dose of scanxiety just adds insult to injury.

Cancer is not something that happens to old people, or rich people, or other people. It happens regardless of where you’re at in life, and the worry about the financial cost adds another dimension to a really shit situation. I can tell you from experience that lying in your hospital bed alternating your worry between whether you are going to die and whether you will be able to pay the mortgage is horrendous. To exponentially increase the cost of doctors visits, medications and scans will mean that some patients simply will not be able to afford the treatments or tests they need.

If you want to register your concern regarding the proposed changes to Medicare, so that every person in this country can afford to access the health care they need to stay alive and live well, here’s what you can do:

- send an email to or telephone your local Federal member and/or state senators – contact details can be found here;

- add your support to the GetUp campaign to protect Medicare;

- think very carefully about how you vote at the next election.